THE WAR YEARs

The war years 1939-1945

he year of 1939 began quietly enough with a visit to the aerodrome by twenty-two officers of the 2nd infantry division of the Aldershot command of the British army. They arrived on the Imperial Airways liner ‘Hannibal’ to watch a tactical exercise.

Over the next few months Hornchurch entertained both French and Romanian Missions, as well as a Siamese military contingent to show the running of a British RAF fighter station.

The ‘Home Defence Exercise’ took place in early August as a prelude of things to come.

The following is an extract taken from the station diary for late August and early September1939:

22.8.39 Instructions received to recall all officers above the rank of Flight Lieutenant.

23.8.39 All regular personnel recalled from leave.

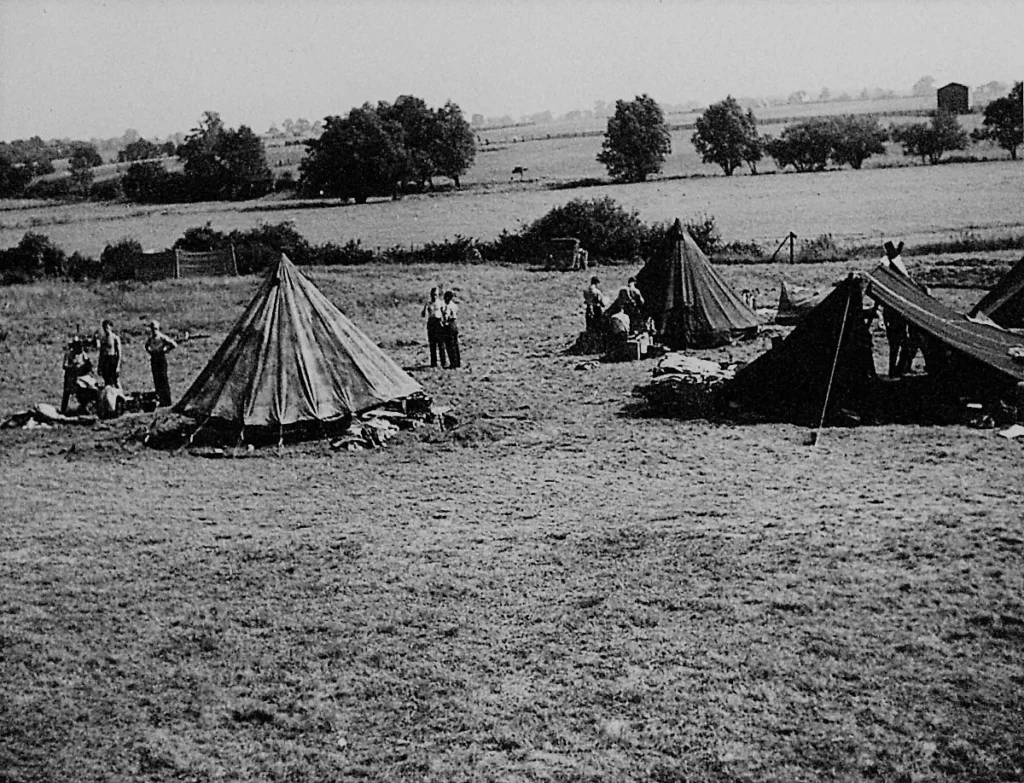

24.8.39 Station defence scheme put into operation and all aircraft of squadrons took up positions at dispersal points. Camouflage of all buildings begun by Works and Buildings, with the operations room manned continuously with a skeleton crew.

25.8.39 fifteen officers arrived on posting for war appointments.

26.8.39 Certain war vehicles collected from Wembley.

27.8.39 Class E’ and Volunteer Reserve personnel begin to arrive.

28.8.39 one officer and forty-four men of the National Defence Guard and arrived to augment the station personnel on guard duties.

31.8.39 Splinter proof boxes placed in position in hanger windows by Works and Buildings.

1.9.39 Operations room manned continuously with complete staff.

2.9.39 General mobilization of the Royal Air Force including the Auxiliary Air Force and Reserves.

Although war had now been declared with Germany, the aerodrome was playing host to a film crew from the London Film Productions, who were shooting some flying sequences with B’ flight of 74 squadron, the semi documentary film revolved around life in fighter and bomber command and was titled ‘The Lion Has Wings’ staring Merle Oberon and Ralph Richardson.

Just three days into the war, on the morning of 6th September 1939, a single aircraft returning from patrol over the English Channel was plotted as ‘hostile’ by the 11 Group controllers at Uxbridge, the Hurricanes of 56 Squadron based at RAF North Weald, were scrambled to intercept the raider. None of the pilots involved had ever seen combat and almost certainly none of them had ever seen an enemy aircraft at this early stage of the war.

The Hurricanes of 56 Squadron became split in their hunt for the so-called ‘intruder’ and in turn, these aircraft were plotted as ‘hostile’ and soon the Ops Room table in Uxbridge became cluttered with ‘hostile’ plots. As a result, further squadrons were scrambled to investigate and Spitfires of 54, 65 and 74 Squadrons from Hornchurch were sent out.

Once the Spitfires of 74 Squadron’s A’ Flight, led by ‘Sailor’ Malan caught sight of one of these suspect plots, Malan ordered ‘Tally Ho’ over the radio, which was the universal signal to attack. Almost as soon as he gave the order, he realised that he had made a mistake – the ‘hostile’ aircraft were in fact two of the Hurricanes of 56 Squadron. In the ensuing melee, both Hurricanes were shot down and although one pilot baled out safely, the other, 26-year-old Pilot Office Montague Hulton-Harrop had the unfortunate distinction of being the first RAF pilot to be shot down and killed over England during the Second World War, albeit by his own side.

Byrne and Freeborn on landing back at Hornchurch were put under arrest and quickly brought before a court martial. Fortunately, both men were acquitted, for it became clear that in the confused atmosphere prevailing on the day, it was impossible to apportion blame. However, this whole affair led to considerable ill-feeling in some quarters. Malan had appeared for the prosecution at the court martial and had accused Freeborn of being irresponsible and of ignoring orders. Freeborn, on the other hand believed that Malan was covering his own back and indeed during the court proceedings, Freeborn’s counsel, Sir Patrick Hastings, accused Malan of being “a bare faced liar.” Remarkably, once the dust of the court martial settled, the two men continued to serve together in 74 Squadron, although not surprisingly relations between the two never recovered.

The incident became known as the ‘Battle of Barking Creek’ although the action took place over rural Essex, nowhere near Barking Creek but as this unattractive feature of east London was the butt of several music hall gags of the time, it was probably inevitable that this misunderstanding would be christened thus by the rank and file of the RAF, who as always showed humour in adversity.

So, after the dramatic start to September, things began to settle down into a long period of inactivity for the Hornchurch squadrons, as their diary entries show the following weeks of the anti-climax in what became a waiting game for the enemy to make its next move. No contact had been made throughout October and even into early 1940, a period that would come to be known as the ‘Phoney War’.

By May of 1940, the German war machine marched across the Dutch, Belgian and French boarders pursuing the British Expeditionary Force back towards the coast and within weeks had driven the British onto the beaches of Dunkirk, surrounded by the German army. With ‘Operation Dynamo’ being put to into action back in England, the plan to evacuate as many troops as possible from under the noses of the Germans using a flotilla of small boats and Naval warships with air support being given by squadrons flying most notably from RAF Hornchurch. This aerial dual was a prelude for things to come, it would also make household names of many of the young pilots flying these dangerous sorties.

An extract from Prime minister Winston Churchill’s speech delivered to the House of Commons on the 18th June 1940, which gave us these now famous words. ‘What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire’. ‘Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say’, “This was their finest hour.”

https://www.winstonchurchill.org/resources/speeches/1940-the-finest-hour/their-finest-hour

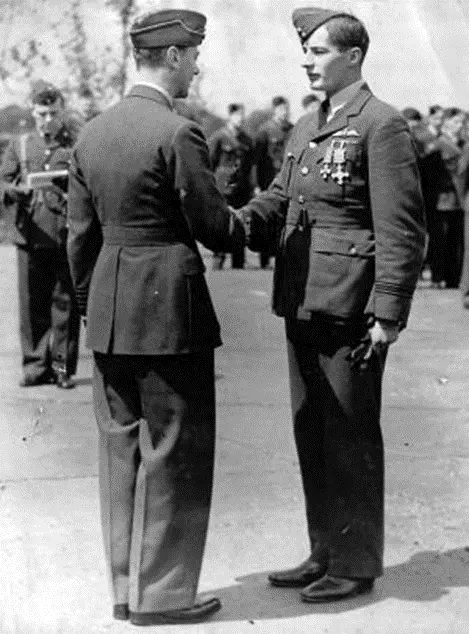

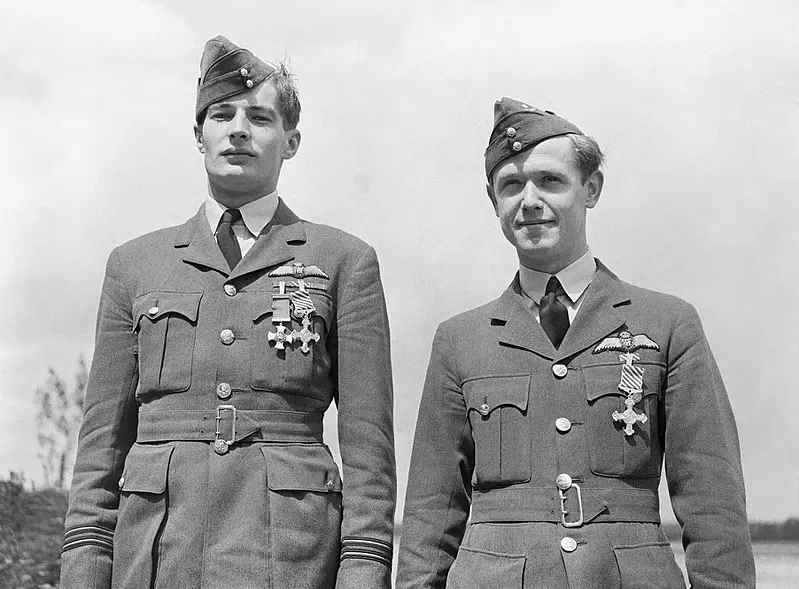

On the 27th June 1940, a very special guest arrived at Hornchurch and unbeknown to the airmen it was His Majesty King George VI, who had come to present medals to some of the gallant heroes that took part in the Dunkirk evacuations by defending the skies over and around the beaches.

The men in question would receive awards for the shooting down enemy aircraft and their bravery in action, they are as follows: P/o Johnny Allen DFC, 54 sqn, F/l Robert Stanford Tuck DFC, 92 sqn, F/l Alan Deere DFC, 54 sqn, F/l Adolph ‘Sailor Malan, DFC, 74 sqn, S/l James Leathart DSO,54 sqn.

By the 10th July 1940, the Battle of Britain had begun, this was to become the greatest aerial combat between to waring nations and would last until the 31st October, this would also be the turning point of the Second World War.

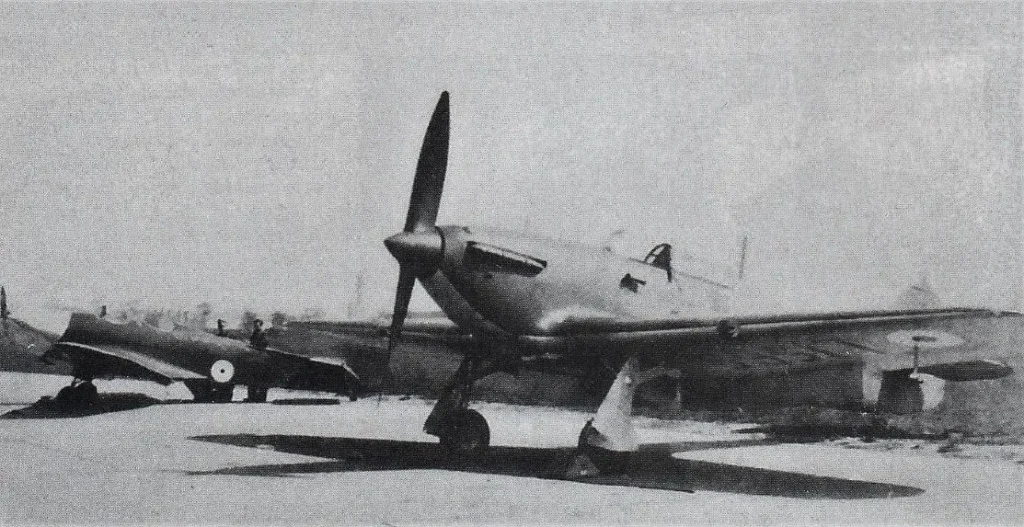

During the Battle of Britain period, all these squadrons flew from RAF Hornchurch aerodrome:

41 squadron, code letters, EB. Spitfire Mk I.

54 squadron, code letters, KL. Spitfire Mk I.

65 East India squadron, code letters, YT. Spitfire Mk I.

74 Trinidad squadron, code letters ZP. Spitfire Mk I.

222 Natal squadron, code letters, ZD. Spitfire Mk I.

264 Madras Presidency squadron, code letters, PS. Boulton Paul Defiant Mk I.

266 Rhodesia squadron, code letters, UO. Spitfire Mk I.

600 City of London squadron, code letters, BQ. Bristol Blenheim Mk IF.

603 City of Edinburgh squadron, code letters, XT. Spitfire Mk I.

From the spring of 1941 through to early 1944, Hornchurch squadrons played a major role in taking part in fighter sweeps (Ramrods) over northern France, as well as seek and destroy missions, (rodeos) and if the weather was bad they made small scale attacks on targets of opportunity (Rhubarbs) these sorties were collectively known as (Circuses). Once the Americans entered the war Hornchurch’s Spitfires were also increasingly called upon to act as escorts for the daylight bombers of the US 8th Army Air Force.

During this time the creation of the ‘Hornchurch Wing’ was formulated, it was a combined force of at least three Spitfire squadrons and often more, that usually operated together en mass on operations over occupied Europe. One of the operations the ‘Wing’ took part in was the provision of escorts to protect air craft making attacks on the German warships ‘Scharnhorst’, ‘Gneisenau’ and ‘Prinz Eugen’ during their dash up the channel. They also supplied fighter cover for the ill-fated Dieppe raid (Operation Jubilee).

During late 1943, the air battles intensified over Europe as the allies began their preparations for the sea invasion, which with luck would take place sometime during early 1944. The Hornchurch Spitfires again had the task of trying to convince the German High Command that any amphibious invasion would take place near Calais and not the planned Normandy beaches. As the date for D-Day approached the Hornchurch squadrons were steadily deployed to forward nearer the proposed landing sites. On February 18th 1944 the Hornchurch operations centre was stood down for the last time, with this fighter operations from Hornchurch aerodrome had all but ended.

Although the aerodrome continued to play in the ongoing war, it became a staging post for the new mobile radar units that would make their way to Europe. It also became home to a maintenance and despatch centre to service vehicles for the allied forces. 567 squadron now called the aerodrome their home, along with 278 Air Sea Rescue squadron and 765 Fleet Air Arm squadron and a signals unit.

The first Vengeance rocket attacks commenced on the 23rd June 1944, when a VI exploded on one of the flightpaths, with a second exploding on the same day came down just outside the aerodromes perimeter. Other VI’s were hitting the suburban areas of East London and were causing heavy damage and casualties and in response 55 Maintenance Repair Unit (MRU) was formed at Hornchurch to help clear bomb sites and repair damaged properties. The 6221 Bomb Disposal Flight (BDF) were also based at the aerodrome.

By March 1945, the threat of the V2 rocket hit home when one came down the new NAAFI building with the blast also damaging the new sergeants mess, airman’s cookhouse and rest room, no casualties were known.

Once hostilities had ceased, Hornchurch still continued to operate as a marshalling depot for service personnel and vehicles, with the site was also being used by Air Training Units.